Why Do We Map Boreal Wetlands?

© DUC. Patterned fen. Dehcho Traditional Territory, NWT. Photo by Rebecca Warren.

By DUC guest writer: Peter Christie

Published: March 2021

CANADA’S BOREAL WETLANDS MATTER. It’s a fact not lost on the National Boreal Program team members at Ducks Unlimited Canada (DUC). Their passion lies in understanding and solving the complex challenges related to the many, often-sprawling areas of water plants, trees, burnished moss and shrubs that are living jewels across the boreal’s nation-spanning wilderness. Threatened caribou forage there, and waterfowl thrive. In the spring, fens of sedge, leatherleaf and Labrador tea fill with songbirds and dragonflies. Wetlands are precious to wildlife and to boreal communities, but their importance has a far larger reach: on a planet that’s lost more than a tenth of its wilderness in just the past two decades[i], the boreal is one of the last strongholds of undisturbed nature left and the natural systems at work in its wetlands are significant to the world[ii].

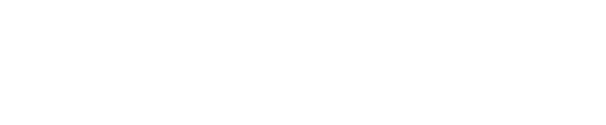

In this article, we explore why describing and mapping Canada’s boreal wetlands is vital. DUC has been at the forefront of this work for decades. More than any other group or agency, DUC has been helping to build Canada’s national inventory of five major wetland classes and—importantly—developing more detailed maps of wetlands (subdivided into 19 classes) and related features across the western boreal known as the Enhanced Wetland Classification System (EWC). To learn more about EWC and the cutting-edge methodology we use to map boreal wetlands, visit How DUC Maps Boreal Wetlands.

© DUC. Mobile technology used to help remote sensing analysts document airborne field surveys.

In this post, we explain how these maps serve as key land-use planning tools, helping people who live and work in the boreal make decisions and act as better wetland stewards. Increasingly, the maps are guiding boreal land managers of every stripe, including First Nations, governments, academics, developers, foresters and other resource industries. They’re used to help spot and address challenges posed by industrial projects or other landscape changes before they threaten the wetlands at the heart of Canada’s magnificent boreal.

Wetland maps as planning tools

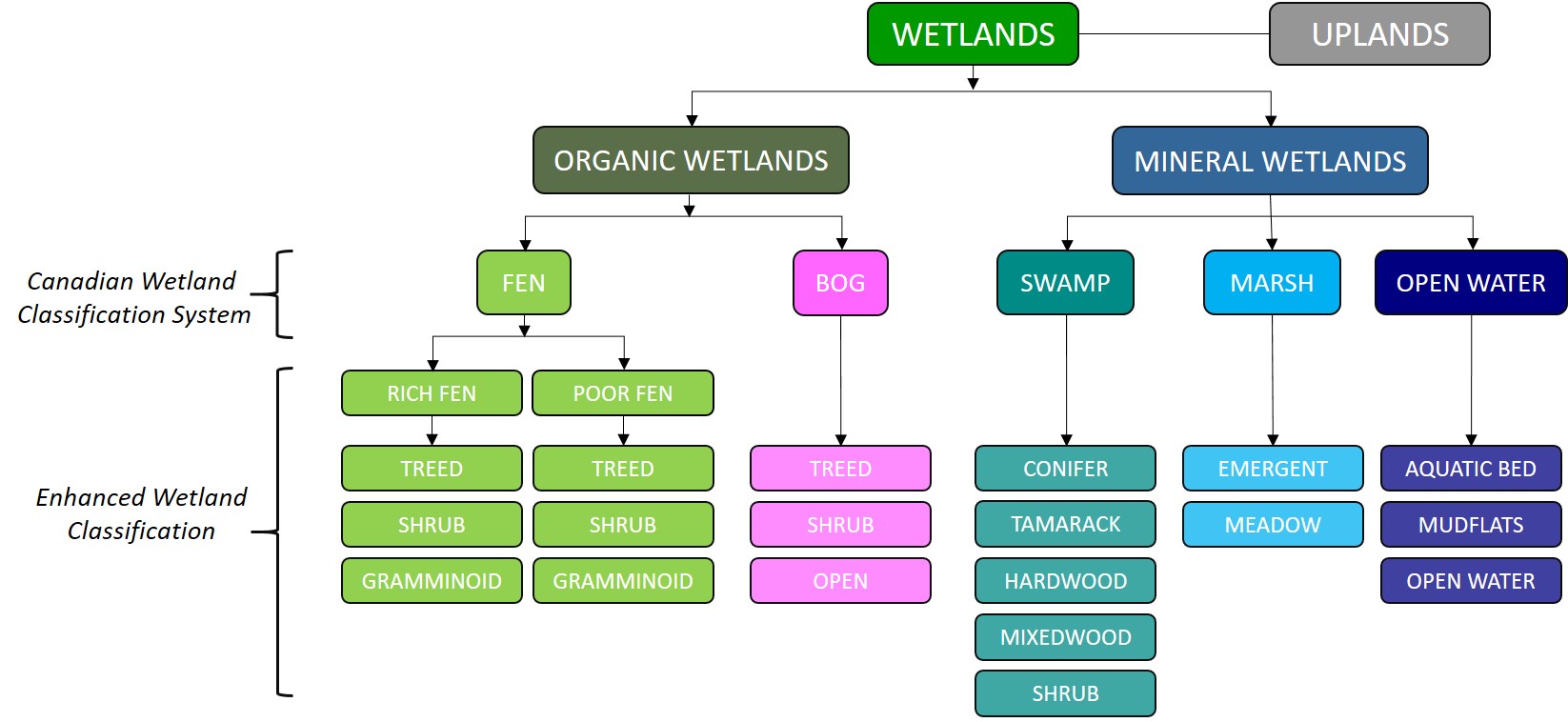

Managing and protecting boreal wetlands requires knowing what and—importantly—where they are. In the Wetlands 101 course, you learned some basic wetland identification skills and became familiar with the five major wetland classes described in the Canadian Wetland Classification System (CWCS). These help us understand a wetland’s characteristic ecology and hydrology as well as something about its importance to the air, water and human needs of the wider area (i.e., the ecosystem goods and services it provides). Identifying these classes also helps policy-makers or developers minimize wetland impacts or answer any challenges the wetlands pose to their work. Mapping them across large areas—and creating an accessible, user-friendly inventory illustrating where each wetland class and type is found—offers a powerful tool for industrial planning, for building and maintaining boreal access roads and other infrastructure, and for meeting environmental regulations and the needs of wildlife. DUC has been mapping the location of the five major wetland classes across much of the western boreal forest for almost two decades. In recent years, maps made according to the Enhanced Wetland Classification (EWC) model that further distinguishes boreal wetlands into 19 wetland categories provides managers and researchers with an even more detailed understanding of the workings and features of boreal wetlands—an understanding essential for their conservation.

© DUC. Extent of DUC wetland inventory (2021).

Need wetland maps?

Through our GIS and Remote Sensing services, DUC has mapped and inventoried large areas of the Canadian Western Boreal region in collaboration with our partners. Many EWC inventories have already been completed and requested information may be provided under varying data use or licensing agreements.

Why map wetlands?

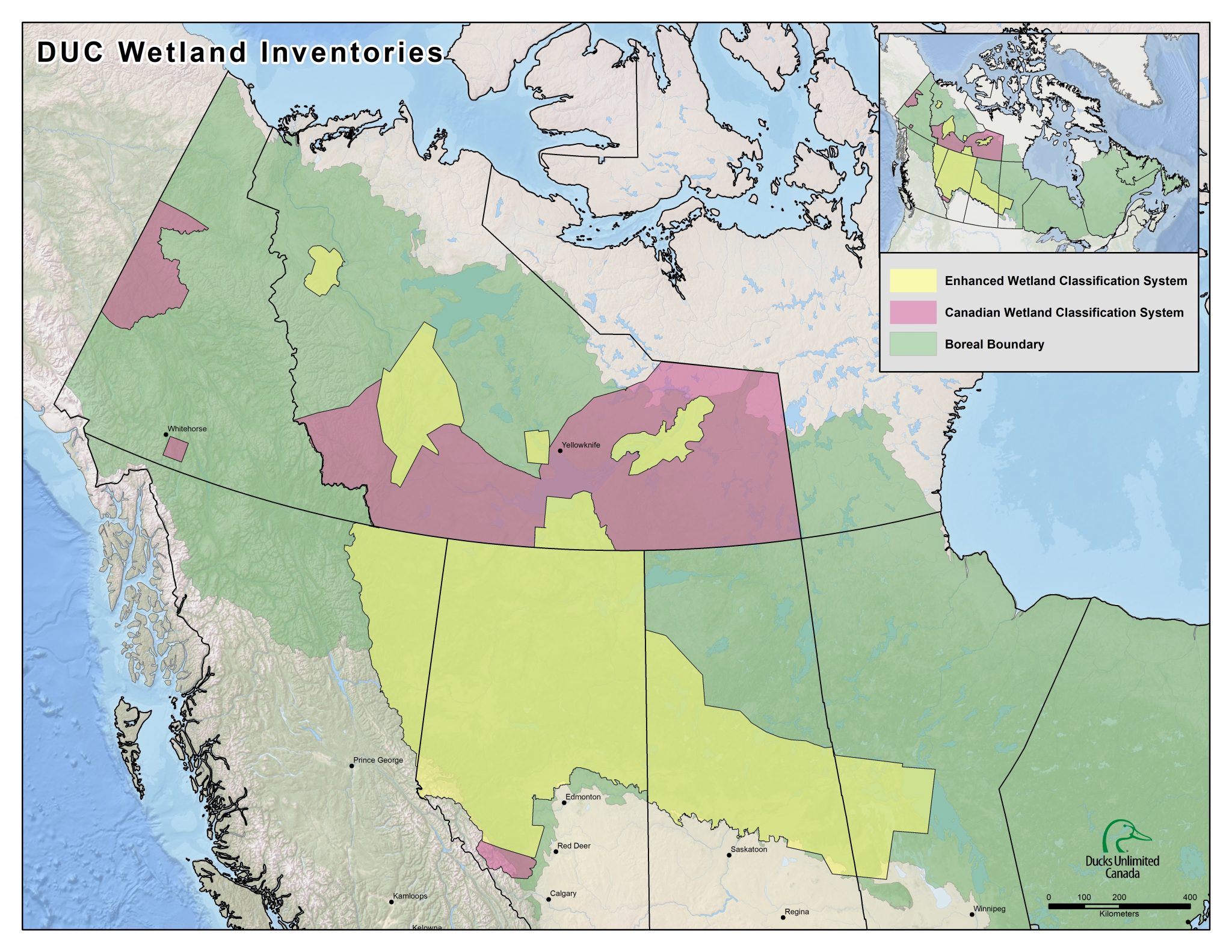

In 2019, when DUC delivered its largest-ever wetland mapping project to members of the Treaty 8 Tribal Corporation (“Akaitcho”) in the south-eastern region of the Northwest Territories, the project’s purpose was never in doubt. By marrying Akaitcho First Nations input with state-of-the-art satellite-generated images, field assessments, reconnaissance flights, and cutting-edge mapping software, the project offered a land-use-planning tool that none could ignore—no matter what culture they hailed from. The Akaitcho First Nations land-use decisions on Akaitcho territory—including what areas to protect and what areas to allow for development—became suddenly easier.

Wetland Classification map of the Akaitcho Traditional Territory in the NWT.

The maps—representing two-and-a-half years of intensive effort by DUC and the Dene communities and technicians—cover 77 million acres of wetlands across Akaitcho traditional lands from the eastern half of Great Slave Lake and to the Nunavut border, a region that’s home to several Indigenous and Métis communities. For generations, these communities have shared the land with pristine nature and boreal wildlife, like the threatened woodland and barren-ground caribou. The maps, which locate and classify wetlands according to Canadian Wetland Classification System (CWCS), offer the Akaitcho First Nations a foundation and a vital path toward self-determination concerning this precious boreal wilderness and their ancestral homeland.

© DUC. DUC and Akaitcho technicians analyze remote sensing data via aerial surveys.

Protecting and managing wetlands is essential. Around the world, wetlands are critical as wildlife hotspots. They’re also vital water cycling and filtration systems, storehouses for climate-altering carbon, and critical, often-sacred places for traditional cultures and communities[iii]. Yet, many of these same wetlands are under siege; globally, between 64 and 71 percent of wetlands (by area) vanished during the last century, and the losses continue.[iv] In Canada, extensive wetland areas in southern regions have also been lost to drainage and development. There, conservation efforts are now focused on restoration. While boreal wetlands remain relatively intact, accelerating northern development and a fast-changing climate mean these pristine places are beginning to face existential threats, too. More than ever, these boreal wetlands—and the more than 500 species of birds, fish and mammals that depend on them—need our careful stewardship.

Mapping plays a critical role. Understanding where boreal wetlands are found, along with useful, timely, and consistent information about their characteristics is key to managing and protecting them. Several European nations and the United States have been describing and mapping wetlands to build standardized national “wetland inventories” for decades[v]. Canada—far larger and far wilder—didn’t formally establish its Canadian Wetland Inventory (CWI) until 2002. The CWI is a collaborative project involving DUC—which has been tracking millions of acres of Canadian wetlands since 1979—along with Environment Canada, the Canadian Space Agency and the North American Wetlands Conservation Council.

How do wetland maps work?

As a work-in-progress, mapping boreal wetlands is a massive job: Canada’s boreal occupies more than a third of this country’s total land area (5.45 million square kilometres) and holds three-quarters of its woodlands[vi] and about 85 percent of its wetlands[vii]. DUC—with its goal to conserve and manage 660 million acres of boreal waterfowl habitat—has nevertheless taken up the challenge. The organization has so far mapped almost 200 million acres throughout the boreal in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Maps for another 300 million acres in the Northwest Territories, Manitoba and Saskatchewan are expected in the coming years. The maps serve as invaluable guides for the use and protection of the boreal’s rich resources and natural splendour.

The amount of information gleaned from wetland maps depends on their level of detail. Historically, DUC’s boreal mapping efforts fall into three categories. First, the Earth Cover Inventory was created to map basic vegetation across parts of the western boreal during the 1990s. In 2002, the creation of the Canadian Wetland Inventory shifted mapping efforts exclusively to wetlands and classified wetlands according to a standardized, five-class model known as the Canadian Wetland Classification System (CWCS). Finally, a few years later, DUC’s national boreal programs manager, Kevin Smith, in partnership with Ducks Unlimited Inc., led the development of the Enhanced Wetland Classification (EWC), improving the level of map detail by further dividing the major CWCS wetlands into 19 separate classes[viii].

© DUC. Hierarchal classification structure for the Canadian Wetland Classification System and Enhanced Wetland Classification.

The CWCS remains widely used and maps Canada’s wetlands according to five separate classes: bogs, fens, swamps, marshes and shallow open water. These classes tell us something about their characteristic ecology and hydrology as well as something about a wetland’s importance to the air, water and human needs of the wider area (i.e., its ecosystem goods and services). While useful to many land managers working in the boreal, the five-class wetland classification offers general but somewhat limited information.

Mapping efforts that use the EWC build on the five-class system by adding information about the types of vegetation present (e.g. trees or shrubs), percentage of vegetation cover, vegetation height and available nutrients (i.e., nutrient rich or poor). The additional classifications not only refine our understanding of each mapped wetland’s characteristics, they contribute to a picture of wetland function and a snapshot of the moisture, water and nutrient dynamics at work there.

How do wetland maps help?

Wetland maps inform boreal planning and management. They’re tools for First Nations, other land managers and anyone else interested in the potential effects of change—manmade or otherwise—across the boreal. Each wetland class represented on a map reveals something about the ground, water and climate that created it. These characteristics, in turn, determine the types and varieties of plants and animals found in the area as well as something about other natural and physical wetland characteristics, such as water flows or the depth of carbon-rich peat.

The detailed, spatially explicit information in DUC’s EWC wetland maps is invaluable to the many land-use planning processes currently underway in regions across the boreal. Balancing environmental, economic and social needs in these plans is tricky, and DUC’s wetland maps—along with decision-support tools for conservation, such as Marxan software—are providing tools that land managers need to solve the challenge of sustainable, wetland-friendly development throughout the boreal.

Need wetland maps? Through our GIS and Remote Sensing services, DUC has mapped and inventoried large areas of the Canadian Western Boreal region in collaboration with our partners. Many EWC inventories have already been completed and are available under varying data use or licensing agreements.

Discover Our Boreal Wetland Inventories

References

[i] Watson, J.E.M., et al. 2016. Catastrophic Declines in Wilderness Areas Undermine Global Environment Targets. Current Biology, 26, 2929-2934.

[ii] Gauthier, S., et al. 2015. Boreal forest health and global change. Science 349: 819-822.

[iii] Junk, W.J. et al. 2013. Current state of knowledge regarding the world’s wetlands and their future under global climate change: a synthesis. Aquatic Sciences 75(1), 151-167.

[iv] Davidson, N. C. (2014). How much wetland has the world lost? Long-term and recent trends in global wetland area. Marine and Freshwater Research, 65(10), 934-941. http://dx.doi.org/10.1071/MF14173

[v] Ramsar Convention Secretariat, 2010. Wetland inventory: A Ramsar framework for wetland inventory and ecological character description. Ramsar handbooks for the wise use of wetlands, 4th edition, vol. 15. Ramsar Convention Secretariat, Gland, Switzerland. 82 pp.

[vi] Bogdanski, B.E.C. 2008. Canada’s Boreal Forest Economy: Economic and Socioeconomic Issues and Research Opportunities. Government of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario. 72 pp.

[vii] Ducks Unlimited Canada. 2018. Field Guide: Boreal Wetland Classes in the Boreal Plains Ecozone of Canada. Version 1.2. Ducks Unlimited Canada, Edmonton, Alberta. 85pp

[viii] Smith, K.B., C.E. Smith, S.F. Forest, and A.J. Richard. 2007. Field Guide to the Wetlands of the Boreal Plains Ecozone of Canada. Ducks Unlimited Canada, Edmonton, Alberta. 96 pp.

About the author

Peter Christie is a science writer and author who writes frequently about conservation. His most recent book is “Unnatural Companions: Rethinking Our Love of Pets in an Age of Extinction”.