Wildlife biologist balances boreal forest conservation and development

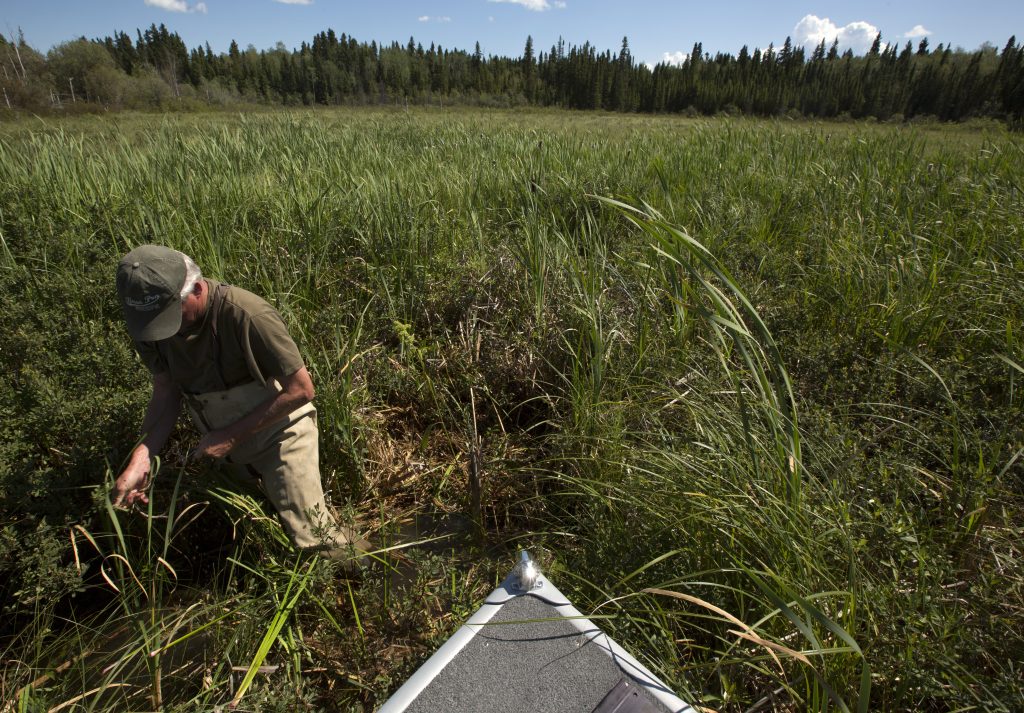

Chris Smith is standing in knee-deep water at the edge of a boreal marsh, surrounded on all sides by thick growths of cattails, reed grass, shrubs, and sedges. As he sloshes through this lush aquatic environment, Smith realizes that his well-worn hip waders are slowly filling with water.

“Just as I predicted, they are leakers,” he announces. Despite this ill-timed outdoor wardrobe malfunction, Smith is grinning.

A wildlife biologist with more than 35 years of experience, Smith relishes any opportunity to share details about the myriad types of wetlands that are found near the edges of First Cranberry Lake in Canada’s boreal forest region.

He points in quick succession to several different varieties—including a shore marsh, a graminoid fen, a shrubby fen, and a hardwood swamp—before regaling a group of visitors with stories about the inside jokes that conservation scientists tell during wetlands training sessions.

“We would just come up with these great terms like, ‘Don’t bog me down,’ and ‘I’m feeling really swamped,’ ” he laughs.

Smith’s good humour and his passion for the outdoors come in handy in his line of work. He heads Ducks Unlimited Canada’s boreal conservation programs, managing the nonprofit group’s science-based efforts to protect forest and wetlands in the region, which stretches across 1.2 billion intact acres in northern Canada.

Smith also leads the work undertaken with forestry companies on ways to improve their environmental practices. This includes raising awareness about the importance of healthy wetlands and the need to ensure environmental prosperity alongside economic prosperity in the resource-rich boreal.

The best part of Smith’s job: He works mostly from a home office tucked amid the trees in Cranberry Portage, a community of 700 that borders Grass River Provincial Park in northern Manitoba. The 560,000-acre park provides critical forest and wetlands habitat for caribou, wolves, bears, waterfowl, and songbirds.

“One of the things that I really appreciate about living in the boreal, having the wilderness around us, is the fact that it’s quiet,” Smith says. “You hear every footstep when you’re walking through the forest.”

Although he was not born in the region, Smith knows the landscape and waterways of the boreal forest intimately. Raised in the prairie city of Winnipeg, the capital of Manitoba, he and his wife, Connie, moved north when Chris was in his 20s. The couple has lived here ever since.

Smith began his career as a field biologist studying the vast wetland complexes of the Saskatchewan River Delta, one of the largest inland deltas in North America. He has flown hundreds of hours in float planes over the boreal region, conducting bird counts and mapping wetlands for Ducks Unlimited Canada. He has also tracked herds of woodland caribou from aircraft and packs of wolves by snowmobile.

“The village of Cranberry Portage is located along an important route that indigenous people used for millennia before the arrival of European traders.”

Smith describes himself and Connie as “northerners by choice.”

The landscape—whether experienced on a walk through the bush, in a boat ride over open water, or in a bush plane flying 100 feet above the tree line—never fails to leave Smith in awe.

“The intactness of the area” is what makes it special, he says. “It doesn’t seem broken to me, you know?”

Yet Smith understands how easily intact landscapes can be lost to unchecked development.

In some southern regions of Canada, he notes, more than 70 percent of wetlands have disappeared. The loss of that habitat has resulted in increased flooding and pollution in one of Canada’s largest lakes, Lake Winnipeg.

Development “is not that rapid up here (in the boreal) at this point, so what a tremendous opportunity [we have] to conserve nature. Rather than thinking about how we’re going to repair something after it’s been negatively impacted … we can think ahead of time about how we can develop wisely,” Smith says.

“There are just not many places like this in the world. It’s one of the largest intact ecosystems on the globe. That doesn’t mean development can’t take place. It means think carefully about it.”

In the boreal, where wetland areas rival the amount of upland forest in ecological importance, Smith says it’s not too late to find a balance that sustains the environment, embraces sustainable development of resources, and maintains healthy communities. The conservation benefits of protecting the boreal extend far beyond Canada’s borders, he says.

“Wetlands store more carbon than the terrestrial environments. When you look at the size of the boreal forest in North America, it’s regulating our global climate and helping offset the implications of climate change. The wetlands in the boreal forest are providing human beings with a lot of services that they probably don’t even realize.”

“The reality is, we’re a natural resource-rich country, and many of those resources are in the boreal forest. And they contribute millions and millions of dollars to our national, provincial, and local economies.”

Though Smith has worked during most of his career with Ducks Unlimited Canada, he also spent a decade employed in the forest sector helping to develop forest management plans that accommodated the interests of both the environment and the people who live in the boreal region. He knows that loggers and conservationists are not always natural allies and that decades-old suspicions between the two sides die hard.

But Smith also believes there is a great opportunity for the two sides to cooperate on sound, comprehensive development and conservation planning in the boreal. The old caricatures—that conservationists oppose cutting down trees, and that loggers want only to clear-cut entire forests—are far outdated, Smith says.

“If people are willing to work together, and identify, and be open about the challenges of development versus conservation, I think wonderful things can happen.”

“A lot of these folks that were doing work in forestry were conservationists themselves. People really did care about (the environmental impacts) of what they were doing and wanted to do the best job they could.”

Smith’s experience in the forest sector has positioned him as a liaison of sorts between conservationists and the resources industries. He values the perspective each side brings to the broader discussion about how the boreal should be managed.

In 2014, he helped produce a Ducks Unlimited Canada operational field guide for forestry companies that were keen to minimize the impact of logging roads built in sensitive boreal wetlands areas.

“To me, it’s unrealistic to think that we can conserve everything, or preserve everything, or develop everything,” he says. “In the past, these were often opposing views: those that are pro-industry versus pro-conservation. The reality is that there’s room for both.”

The communities surrounding his home in Cranberry Portage, he says, would not exist without industry.

To the north of Cranberry Portage, the small city of Flin Flon relies on mining. To the south, the town of The Pas depends heavily on forestry to drive the economy. Many of the forest products that North Americans take for granted, Smith notes, originate in the boreal.

“The reality is, we’re a natural resource-rich country, and many of those natural resources are in the boreal forest. And they contribute millions and millions of dollars to our national, provincial, and local economies,” he says.

“I get to go to a Canadian Tire and I get to go to a Wal-Mart 30 miles from my home. Although this may not seem like a big deal to many people, those stores and those services would not be here if there wasn’t a viable forestry and mining industry. … People make a good living. They have a good lifestyle.”

And, increasingly, the people who live in the boreal are demanding a seat at the table when decisions are being made about the region’s future.

Industry has a responsibility to ensure that development is “sensitive to the ecosystem itself, as well as the communities that are there, and some of these communities have been here for a very long time—like the indigenous communities,” Smith says.

“More and more, northerners want to have a say in the way their backyard is being developed.”

“There are just not many places like this in the world. It’s one of the largest intact ecosystems on the globe. That doesn’t mean development can’t take place. It means think carefully about it.”

Smith’s conservation ethic has guided the way he lives his life away from work.

He and Connie moved from The Pas to Cranberry Portage six years ago, built a home at lake’s edge, and plan to retire here. The area marks the dividing line between two major geological regions: the generally flat boreal plains, which feature abundant wetlands, and the more rocky landscape of the boreal shield.

Rather than cut down a lot of trees to gain an unobstructed view of the lake, the couple left the shoreline of shrubs, birch, and spruce in place. The tree cover not only protects their home from winter winds blowing in off the lake, but it also maintains habitat for forest critters such as squirrels and pileated woodpeckers.

“We wanted to retain as much of the natural forest around our home as possible,” he says. “It drove our contractors nuts, but … there’s more thermal cover for retaining heat in the winter and keeping it cooler in the summer.”

The Smiths’ home includes a studio for Connie, a stained-glass artist who specializes in creating nature scenes that reflect the boreal environment in which the couple lives. The house is adorned with stained-glass depictions of songbirds and waterfowl that populate the area.

“What really attracts me, personally, to this area and why we both want to live here is the relative isolation. We are not city people. We don’t like the hustle and bustle. Having a peaceful place that’s relatively untouched is very important to us,” Chris Smith says.

“I always say the best part about cities is leaving them. We’ve said many times driving from the south that when we start to get into the bush, that it starts to feel like we’re coming home.”

“Wetlands store more carbon than the terrestrial environments. When you look at the size of the boreal forest in North America, it’s regulating our global climate and helping offset the implementation of climate change. The wetlands in the boreal forest are providing human beings with a lot of services that they probably don’t even realize.”

Original article from The Pew Charitable Trusts. Permission to republish granted to DUC by The Pew Charitable Trusts. Photos by the Pew Charitable Trusts.

Cutlines: na

Photo credits:

© THE PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS/KATYE MARTENS